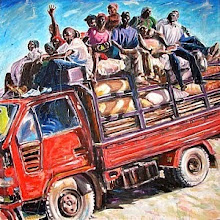

The Dublin of today is a far cry from the Dublin of the 1980s when it was said to resemble London directly after the Second World War, so numerous were its run-down buildings and empty sites. In the last 10-15 years much of the city has been renovated or rebuilt. The success of the ‘Celtic Tiger’ has given the Irish people historically unprecedented wealth and attracted many immigrants from all over the world. This can all be seen in a brief walk around the city centre. The new (and expensive) cars glide past African and Polish shops while people from many different ethnic and cultural backgrounds mingle around the Spire and the GPO on O’Connell St.

The Dublin we see today is a snapshot in time, hiding its past while only leaking hints of where its future will lie. For example, the new O’Connell St with its squared-off designer trees and generous paving hides the felling only the year before of a row of 100-year-old trees that witnessed the 1916 Easter Rising. Looking to the future it seems likely that Liberty Hall, Dublin’s only modernist ‘skyscraper’ and prominent if unloved symbol of Dublin, will be demolished soon in favour of a more modern or even postmodern replacement.

The Dublin of today has many contrasts, symbolic of shambolic planning yet with many hopeful idealists struggling against the odds. Witness the Liffey Boardwalk in contrast with the traffic-jammed quays; the huge reduction of plastic signs (the scourge of the 1970s and 1980s) in contrast with the monotony of quick-rise apartment block and shopping centre developments.

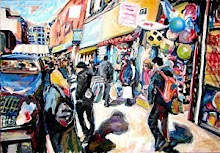

Yet older areas of the city like Moore St and Parnell St, which were going into decline as the more affluent Irish moved to greener pastures, are seeing extraordinary multicultural changes as immigrants set up shops and restaurants with a never-before-seen range of food, goods and menus. Indeed the culinary tastes of the new visitors and inhabitants have created a demand for exotic vegetables, fruit and seafood never even contemplated by their Irish neighbours.

The relatively recent wealth of Dublin and many of its citizens (symbolized by the number of Brinks vans leaving the cosmopolitan Grafton St as shoppers enter it) may also be a snapshot in time as the uncertain economic future of rising interest rates, peak oil, and global warming threatens to bring the whole economic façade tumbling down like the crumbling slum dwellings of the 1960s.

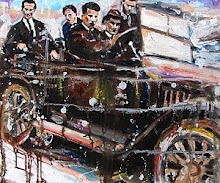

The statues of historical figures such as Jim Larkin, Daniel O’Connell, Charles Stewart Parnell, and James Connolly look down on a new city that sits uncomfortably with their varieties of nationalism and socialism.

These symbols of the past, standing in silent judgment of the follies of the present, act as control rods in the current economic fission reminding its old and new, wealthy and poor citizens alike of past struggles and hardships.

Tuesday, April 3, 2007

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)