Caoimhghin Ó

Croidheáin gaelart.net

'Sord of Columcille' / 'Swrth Colomkelle' / 'Sord' / 'Surd' / 'Suird' / 'Sords' / 'Swerts'

/ 'Swerds'

/ 'Sweerdes' / 'Swordes' / 'Swords'

Gaelic: Sord Cholmcille - St. Colmcille's Well

For a more detailed history and over 70 images of Swords see: http://gaelart.net/swords.html

The town's origins date back to 560 AD when it was founded by Saint

Colmcille (521-567). Legend has it that the saint blessed a local well,

giving the town its name, Sord, meaning "clear" or "pure". However, An

Sord also means "the water source" and could indicate a large communal

drinking well that existed in antiquity. St. Colmcille's Well is located

on Well Road off Swords Main Street.

(See below for usage of different

spellings in texts etc.)

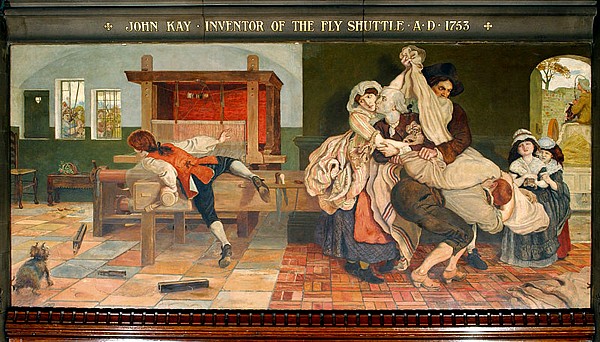

Tower, Belfry and Church (1790s)

For more information see:

http://discovery.dho.ie/navigation.php?navigation_function=2&navigation_item=ria_3+C+31/13

"The original word is properly written "Sord," or "Surd," which is

interpreted "clear," or "pure," although in modern Irish the word so

spelt bears the meaning of "order ... industry ... diligence." The w

came into it after the settlement of the English, who wrote the name

Swerds, though pronounced Swords, as the verb shew has the

sound of show. This interpretation which I give you is from an ancient

Life of St. Columbkille, preserved in a very venerable MS. of the Royal

Irish Academy, of the fourteenth century. [...] it was the practice of

the early founders of Christianity in these islands, when planting a

church in any spot, to have special reference to the proximity of a

well. [...] suffice it to say, that well-worship existed in the country

before the introduction of Christianity, and that when the people were

converted, like the transfer of pagan temples, these wells, with all

their veneration, were made over to the aid of the new religion."

(See A Lecture on the Antiquities of Swords by The

Late Right Rev. William Reeves below)

Tower, Belfry and Church.

'Published by T Hooper June 11th 1791 Engraved by Jas Newton'

Early History

'Suird' (usage in ancient texts)

Baile Bricín

Baile Bricín ("The Vision of Bricín") is a late Old Irish or Middle

Irish prose tale, in which St Bricín(e), abbot of Túaim Dreccon (Tomregan),

is visited by an angel, who reveals to him the names of the most

important future Irish churchmen (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baile_Bric%C3%ADn).

Saint Bricín (c.590–650; also known as Bricin, Briccine, DaBreccoc,

Da-Breccocus) was an Irish abbot of Tuaim Dreccon in Breifne (modern

Tomregan, County Cavan), a monastery that flourished in the 7th century

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bric%C3%ADn).

Tascor mara aidche mBuilt

tidnastar dó ind-Inbiur Suird,

bid ór, bid arcad, bud glain,

bid fín mbárc ó Rómánchaib.

http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/G207008/text001.html

http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/G207008/

Translation:

A fleet from across the sea at night in Built

which will be delivered up to him in the estuary of Sord.

It will be gold, it will be silver, it will be crystal

It will be a wine-ship from (the) Romans.

https://listserv.heanet.ie/cgi-bin/wa?A3=ind0502&L=OLD-IRISH-L&E=quoted-printable&P=345518&B=--&T=text%2Fplain;%20charset=ISO-8859-1

The Book of Leinster

The following list is from the 12th-century The Book of Leinster,

formerly Lebar na Núachongbála list of abbesses and other

ecclesiastics and their communities owing allegiance to Kildare (pp.

1580-1583, cf. Corpus genealogiarum sanctorum Hiberniae, 112-18,

210-12). Most of the sites are near Kildare in Leinster although some

were as far away as Sligo and Tyrone.

29. Dísert Brigte in Cell Suird (near Swords, co. Dublin)

http://www.monasticmatrix.org/monasticon/cell-dara

Swords Castle.

'Published by T Hooper August 9th 1791 Engraved by Jas Newton'

Annals of the Four Masters

The Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland (Irish: Annála Ríoghachta

Éireann) or the Annals of the Four Masters (Annála na gCeithre Máistrí)

are a chronicle of medieval Irish history. The entries span from the

Deluge, dated as 2,242 years after creation to AD 1616. The annals are

mainly a compilation of earlier annals, although there is some original

work. They were compiled between 1632 and 1636 in the Franciscan friary

in Donegal Town. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annals_of_the_Four_Masters).

We read in the Annals of the Four Masters, that Dun-Sobhairce was among

the first fortresses erected in this island by the Milesians:--

A. M. 3501. "This is the year in which Heremon and Heber assumed the

joint government of Ireland, and divided Ireland equally between them.

In it also the following fortresses, &c. were erected, viz.

Rath-beathaigh, on the banks of the river Nore, in Argatros, (now

Rathveagh, within five miles of Kilkenny; (Rath-oin, in the territory of

Cualann, (now the County Wicklow;) the causeway of Inbhear-mor, (now

Arklow;) the house in Dun-nair. on the Mourne mountains. Dun-Delginnis,

in the territory of Cualann, (now Delgany, Co. Wicklow;) DUN SOBHAIRCE,

in Murbholg of Dalriada, (Dunseveric,) was erected by Sovarke; and Dun

Edair, (on the Hill of Howth,) by Suighde; all these foregoing were

erected by Heremon and his Chieftains. Rath-Uamhain, in Leinster;

Rath-arda, Suird, (Swords;) Carrac Fethen, Carrac Blarne, (Blarney,)

Dun-aird Inne, Rath Riogbhard, in Murresk, were erected by Heber and his

chieftains."

http://www.oracleireland.com/Ireland/Countys/antrim/z-dunseverick-dublin.htm

See also:

http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/T100005A/text005.html

http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/T100005A/

Sord of Columcille / Sord / Swerts

(usage in ancient texts)

Annals of the Four Masters

The Battle of Clontarf, Brian Boru and his wake at Swords

1013 [Annal M1013.11]

An army was led by Brian, son of Ceinneidigh, son of Lorcan, King of

Ireland, and by Maelseachlainn, son of Domhnall, King of Teamhair, to

Ath-cliath. The foreigners of the west of Europe assembled against Brian

and Maelseachlainn; and they took with them ten hundred men with coats

of mail. A spirited, fierce, violent, vengeful, and furious battle was

fought between them, the likeness of which was not to be found in that

time,—at Cluaintarbh, on the Friday before Easter precisely. In this

battle were slain Brian, son of Ceinneidigh, monarch of Ireland, who was

the Augustus of all the West of Europe, in the eighty-eighth year of his

age; Murchadh, son of Brian, heir apparent to the sovereignty of

Ireland, in the sixty-third year of his age; Conaing, son of Donncuan,

the son of Brian's brother; Toirdhealbhach, son of Murchadh, son of

Brian; Mothla, son of Domhnall, son of Faelan, lord of the Deisi-Mumhan;

p.775

Eocha, son of Dunadhach, i.e. chief of Clann-Scannlain; Niall Ua Cuinn;

Cuduiligh, son of Ceinneidigh, the three companions of Brian; Tadhg Ua

Ceallaigh, lord of Ui Maine; Maelruanaidh na Paidre Ua hEidhin, lord of

Aidhne; Geibheannach, son of Dubhagan, lord of Feara-Maighe; Mac-Beatha,

son of Muireadhach Claen, lord of Ciarraighe-Luachra; Domhnall, son of

Diarmaid, lord of Corca-Bhaiscinn; Scannlan, son of Cathal, lord of

Eoghanacht-Locha Lein; and Domhnall, son of Eimhin, son of Cainneach,

great steward of Mair in Alba. The forces were afterwards routed by dint

of battling,

p.777

bravery, and striking, by Maelseachlainn, from Tulcainn to Ath-cliath,

against the foreigners and the Leinstermen; and there fell Maelmordha,

son of Murchadh, son of Finn, King of Leinster; the son of Brogarbhan,

son of Conchobhar, Tanist of Ui-Failghe; and Tuathal, son of Ugaire,

royal heir of Leinster; and a countless slaughter of the Leinstermen

along with them. There were also slain Dubhghall, son of Amhlaeibh, and

Gillaciarain, son of Gluniairn, two tanists of the foreigners; Sichfrith,

son of Loder, Earl of Innsi hOrc; Brodar, chief of the Danes of Denmark,

who was the person that slew Brian. The ten hundred in armour were cut

to pieces, and at the least three thousand of the

p.779

foreigners were there slain. It was of the death of Brian and of this

battle the following quatrain was composed:

Thirteen years, one thousand complete, since Christ was born, not long

since the date, Of prosperous years—accurate the enumeration—until the

foreigners were slaughtered together with Brian. Maelmuire, son of

Eochaidh, successor of Patrick, proceeded with the seniors and relics to

Sord-Choluim-Chille; and they carried from thence the body of

p.781

Brian, King of Ireland, and the body of Murchadh, his son, and the head

of Conaing, and the head of Mothla. Maelmuire and his clergy waked the

bodies with great honour and veneration; and they were interred at

Ard-Macha in a new tomb.

http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T100005B/index.html

Swords Castle. Mrs Hall Travels around Ireland (1843)

More references from Annals of the Four Masters

965 [M965.2 Ailill, son of Maenach, Bishop of Sord and Lusca;]

[celt]

993, "Sord of Columcille was burned by Maolsechlain."

[Reeves]

1016, "Sord of Columcille was burned by Sitric, son of Aniat, and the

Danes of Dublin." [Reeves]

1020 [M1020.6 The burning of Cluain-Iraird, Ara, Sord, and

Cluain-mic-Nois.] [celt]

1020, "Sord of Columcille was plundered by Connor O Maclachlann, who

burned it, and carried away many captives, and vast herds of cows."

[Reeves]

1023. Maelmaire Ua Cainen, wise man, and Bishop of

Sord-Choluim-Chille, died [archive.org]

1028. Gilla- christ, son of Dubhchuillinn, a noble priest of Ard-Macha,

died at Ros-Commain.

Coiseanmach, son of Duibheachtgha, successor of Tola ; Gillapadraig Ua

Flaith- bheartaigha, airchinneach of Sord ; Cormac, priest of

Ceanannus ; Maelpadraig Ua Baeghalain, priest of Cluain-mic-Nois ;

Flaithnia Ua Tighernain, lector of Cill-Dacheallog w ; and Cearnach,

Ostiarius of Cluain-mic-Nois, died. [archive.org]

1031, "Sord of Columcille was burned and plundered by Connor

O'Maclachlann, in revenge for the death of Raghnall, son of Ivar, Lord

of Waterford, by the hand of Sitric, son of Anlaf." [Reeves]

1034 Conn macMaelpatrick, Sord-Choluim-Chille [archive.org]

1035 Raghnall, grandson of Imhar, lord of Port-Lairge, was slain at

Ath-cliath by Sitric, son of Amhlaeibh ; and Sord Choluim Chille

h was plundered and burned by Con-chobhar Ua Maeleachlainn, in revenge

thereof. [archive.org] [M1035.4 Ardbraccan was plundered by Sitric

afterwards, and Sord Choluim Chille was plundered and burned by

Conchobhar Ua Maeleachlainn, in revenge thereof.] [celt]

1042, "died Eochagan, herenach

of Slane, Lector of Sord, and a distinguished writer." [Reeves]

[M1042.3 Eochagan, airchinneach of Slaine, and lector of Sord,

and a distinguished scribe;] [celt]

1045, "An army was led by M'Eochaidh and Maolsechlann, with the

foreigners who burned Sord, and wasted Fingall." [Reeves]

1048 Aedh, son of Maelan Ua Nuadhait, airchinneach of Sord, was

killed on the night of the Friday of protection before Easter, in the

middle of Sord. [archive.org]

1056, "the fire of God (that is, lightning) struck the Lector of Sord, and tore asunder the sacred tree."

[Reeves] Lightning appeared and killed three at Disert-Tola, and a

learned man at Swerts" [Swords], "and did breake the great tree.

[archive.org]

1060 Maelchiarain Ua Robhachain, airchinneach of Sord-Choluim-Chille

; and Ailill Ua Maelchiarain, airchinneach of Eaglais-Beg [at

Cluain-mic-Nois], died. [archive.org]

1061 Mael- incited these of Delvyn-Beathra, with their kiaran O'Robucan,

Airchinnech of Swerts" king, Hugh O'Royrck, in their pursuite,

who [Swords], "mortuus est. [archive.org]

1069, "Lusc and Sord of Columcille were burned."

[Reeves] [M1069.4 Dun-da-leathghlas, Ard-sratha, Lusca, and

Sord-Choluim-Chille, were burned.] [celt]

1102, "Sord of Columcille was burned." [Reeves]

1130, "Sord of Columcille, with its churches and relics, was burned."

[Reeves] [M1130.1 Sord-Choluim-Chille, with its churches and

relics, was burned.] [celt]

1136 [M1136.6 Mac Ciarain, airchinneach of Sord, fell by the men

of Fearnmhagh.] [celt]

1138, "Sord burned." [Reeves] [M1138.3 Cill-dara,

Lis-mor, Tigh-Moling, and Sord, were burned.] [celt]

1150, "Sord burned." [Reeves] [M1150.6 Ceanannus,

Sord, and Cill-mor-Ua-Niallain,with its oratory, were burned.] [celt]

1166, "Sord of Columcille was burned." [Reeves]

[M1166.8 Lughmhadh, Sord-Choluim-Chille, and Ard-bo, were

burned.] [sord]

References

[Reeves] See: A Lecture on the Antiquities of Swords below.

[celt] See:

http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T100005B/index.html

[archive.org] See:

http://archive.org/stream/annalarioghachta01ocleuoft/annalarioghachta01ocleuoft_djvu.txt

The Medieval Latin Life of Gruffudd Ap Cynan

Gruffudd ap Cynan (c. 1055 – 1137) was a King of Gwynedd. In the

course of a long and eventful life, he became a key figure in Welsh

resistance to Norman rule, and was remembered as King of all Wales.

According to the Life of Gruffudd ap Cynan, Gruffudd was born in Dublin

and reared near Swords, County Dublin in Ireland.

Unusually for a Welsh king or prince, a near-contemporary biography of

Gruffudd, The history of Gruffudd ap Cynan, has survived. Much of

our knowledge of Gruffudd comes from this source, though allowance has

to be made for the fact that it appears to have been written as dynastic

propaganda for one of Gruffudd's descendants. The traditional view among

scholars was that it was written during the third quarter of the 12th

century during the reign of Gruffudd's son, Owain Gwynedd, but it has

recently been suggested that it may date to the early reign of Llywelyn

the Great, around 1200. The name of the author Is not known.

Most of the existing manuscripts of the history are in Welsh but these

are clearly translations of a Latin original. It is usually considered

that the original Latin version has been lost, and that existing Latin

versions are re-translations from the Welsh. However Russell (2006) has

suggested that the Latin version in Peniarth MS 434E incorporates the

original Latin version, later amended to bring it into line with the

Welsh text (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gruffudd_ap_Cynan).

"Cum in Anglia regnaret Edwardus dictus Confessor et apud Hybernos

Therdelachus rex, nascitur in Hybernia apud civitatem Dublinensem

Griffinus rex Venedotiae, nutriturque in loco Comoti Colomkelle dicto

Hybernice Swrth Colomkelle, per tria miliaria distante a duomo

suorum parentum."

(Translation from Latin)

"When Edward (called the Confessor) was ruling in England and King

Toirrdelbach was ruling over the Irish, there was born in Ireland in the

city of Dublin, Gruffudd, king of Gwynedd, and he was fostered in a

place in the commote of Colum Cille called in Irish Sord Coluim

Chille, which lies three miles away from the home of his parents."

Source: Vita Griffini Filii Conani: The Medieval Latin Life of

Gruffudd Ap Cynan, edited and translated by Paul Russell, University

of Wales Press, 2005 (reprinted 2012), pp.53-54

The Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 23, December 1, 1832.

The Round Tower of Swords

From The Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 23, December 1, 1832.

The ancient town of Swords, situated in the barony of Coolock, about

seven miles from the metropolis, though now reduced to an insignificant

village, is remarkable for its picturesque features, its ruins, and its

historical recollections. Its situation is pleasing and romantic, being

placed on the steep banks of a small and rapid river, and though its

general appearance indicates but little of prosperity or happiness, its

very ruins and decay, give it, at least to the antiquary and the

painter, a no common interest.

Like most of our ancient towns Swords appears to be of ecclesiastical

origin. A sumptuous monastery was founded here in the year 512, by the

great St. Columb, who appointed St. Finian Lobair, or the leper, as its

abbot, and to whom he gave a missal, or copy of the gospels, written by

himself. St. Finian died before the close of the sixth century. In

course of time this monastery became possessed of considerable wealth,

and the town rose into much importance. It contained within its

precincts, in addition to St. Columb's church, four other chapels, and

nine exterior chapels subservient to the mother church. Hence on the

institution of the collegiate church of St. Patrick, it ranked as the

first of the thirteen canonries attached to that cathedral by archbishop

Comin, and was subsequently known by the appellation of "the golden

prebend." There was also a nunnery here, the origin of which is unknown.

To this monastery the bodies of the monarch Brian Boru, and his son

Morogh, were conveyed in solemn procession by the monks, after the

memorable battle of Clontarf, and after remaining a night, were carried

to the abbey of Duleek, and committed to the care of the monks of St.

Cianan, by whom they were conveyed to Armagh.

Swords was burnt and plundered frequently, as well by the native

princes, as by the Danes, who set the unholy example. By the latter it

was reduced to ashes in the years 1012, and 1016, and by the former in

the years 1035 and 1135. On this last occasion the aggressor, Conor

O'Melaghlin, king of Meath, was slain by the men of Lusk. Its final

calamity of this kind occurred in the year 1166.

Here it was that the first Irish army of the Pale assembled on the

9th of November, 1641, preparatory to that frightful civil war which

caused such calamities to the country; and here they were defeated and

put to the rout by the forces under Sir Charles Coote, on the 10th of

January following, when he beat them from their fortifications and

killed two hundred of them, without any material loss, except that of

Sir Lorenzo Carey, second son of Lord Falkland, who fell in the

engagement.

Of the numerous ecclesiastical edifices for which Swords was

anciently distinguished, the only remains now existing are those

represented in the prefixed engraving--for the castle, though said to

have been the residence of the archbishop of Dublin can hardly be

included under this denomination. These consist of a fine and lofty

round tower, coeval with the foundation of the original monastery, and

the abbey belfry, a square building of the fourteenth or fifteenth

century. The former is seventy-three feet high, fifty-two feet in

circumference, and the walls four feet thick. It contained five stories,

or floors. Its present entrance which is level with the ground, is of

modern construction, as well as the roof and upper story: what appears

to have been the original doorway is twenty feet from the ground, and

but four feet high. Respecting the uses of those singular ancient

buildings, we deem it improper to express any opinion, till the Royal

Irish Academy shall have announced its decision on the prize essays on

this subject, now under its consideration.

These two towers with the adjacent church, form a picturesque and

uncommon architectural group; but the church which is of modern

erection, having been completed in the year 1818, though imposing in its

general appearance, is but a spurious and jejune imitation of the

pointed or gothic style of architecture, and such as might have been

expected from minds so wanting in good taste and feeling as those which

permitted the removal of the beautiful ruins of the ancient abbey to

erect it on their site. Similar acts of wanton destruction are now

unfortunately of daily occurrence, and are anything but honorable to

their perpretrators, who, though they may regard such remains as

vestiges of ancient superstition, should still remember, as Byron says,

that

----"Even the faintest relics of a shrine

Of any worship, wake some thoughts divine."

We are told that the inhabitants of Swords feel proud of this

pretending, but tasteless structure, and we believe it possible; but if

the principles of a refined and educated architectural taste should ever

again be generally disseminated in Ireland, they will indulge in a very

different feeling. In this country we have yet to learn that elegance of

form and correctness of design in ecclesiastical buildings are, in the

hands of a judicious and educated architect, quite attainable, even with

the limited means usually appropriated to the purpose.

We shall give a view and account of the castle, or episcopal palace

of Swords, in a future number.

G.

For more information see:

http://www.libraryireland.com/articles/RoundTowerSwordsDPJ1-23/index.php

'Sord' 'Sords' (early usage)

History of the Christian Church by Philip Schaff (7 vols., 1858–1890)

"Saint Columba or Columbcille, (died June 9, 597) is the real apostle of

Scotland. He is better known to us than Ninian and Kentigern. The

account of Adamnan (624-704), the ninth abbot of Hy, was written a

century after Columba's death from authentic records and oral

traditions, although it is a panegyric rather than a history. Later

biographers have romanized him like St. Patrick. He was descended from

one of the reigning families of Ireland and British Dalriada, and was

born at, Gartan in the county of Donegal about a.d. 521. He received in

baptism the symbolical name Colum, or in Latin Columba (Dove, as the

symbol of the Holy Ghost), to which was afterwards added cille (or kill,

i.e. "of the church," or "the dove of the cells," on account of his

frequent attendance at public worship, or, more probably, for his being

the founder of many churches.79 He entered the monastic seminary of

Clonard, founded by St. Finnian, and afterwards another monastery near

Dublin, and was ordained a priest. He planted the church at Derry in

545, the monastery of Darrow in 553, and other churches. He seems to

have fondly clung all his life to his native Ireland, and to the convent

of Derry. In one of his elegies, which were probably retouched by the

patriotism of some later Irish bard, he sings:

"Were all the tributes of Scotia [i.e. Ireland] mine,

From its midland to its borders,

I would give all for one little cell

In my beautiful Derry.

For its peace and for its purity,

For the white angels that go

In crowds from one end to the other,

I love my beautiful Derry.

For its quietness and purity,

For heaven's angels that come and go

Under every leaf of the oaks,

I love my beautiful Derry.

My Derry, my fair oak grove,

My dear little cell and dwelling,

O God, in the heavens above I

Let him who profanes it be cursed.

Beloved are Durrow and Derry,

Beloved is Raphoe the pure,

Beloved the fertile Drumhome,

Beloved are Sords and Kells! [inmhain Sord as Cenanddus [Betha

Colaim chille] (1918)]

But sweeter and fairer to me

The salt sea where the sea-gulls cry

When I come to Derry from far,

It is sweeter and dearer to me —

Sweeter to me."

http://www.bible.ca/history/philip-schaff/4_ch02.htm

Tower and Belfry (c.1794)

Tower and Belfry (c.1794)

For more information see:

http://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000147923

Betha Choluim Chille / The Life of Colum Cille [P. 114]

Fothaigis eclais isin inad h-itá Sord indiú. Fácbais fer

sruith diá muntir and .i. Finan Lobur. & facbais in soscéla ro scrib a

lám fodessin. Tóirnis tra ann tipra dia n-ainm Sord .i. glan. &

senais croiss.

http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/G201011/

(Translation)

"Colum Cille founded a church there, and that is 'Swords of Colum

Cille' today. Colum Cille left a good man from his own household

there as his successor, Finan the Leper, and he left there the missal

which he himself had written. Colum Cille blessed Swords and he

blessed its well - Glan ['Clean'] is its name - and he left a cross

there."

The Life of Colum Cille by Manus O'Donnell [1532] [ed. Brian Lacey]

(Four Courts Press, Dublin 1998)

See also

http://archive.org/stream/bethacolaimchill00odonn#page/98/mode/2up

'Sords' (usage of 'Sords' spelling on a gravestone)

This stone was erected by Rob Willon of Sords in

memory of his father

William Willon who departed

this life Nov. 6th 1750 aged 57 [...] their

posterity.

(St Columba's Church of Ireland graveyard, Swords)

A Lecture on the Antiquities of Swords by The

Late Right Rev. William Reeves

THE ANTIQUITIES OF SWORDS 1970 A LECTURE ON THE ANTIQUITIES OF SWORDS

Delivered at Swords, in the Borough Schoolhouse on Wednesday Evening.,

Sep. 12, 1860, by THE LATE RIGHT REV. WILLIAM REEVES D.D., L.L.D., M.B.,

M.R.I.A.; Bishop of Down; formerly Vicar of Lusk

[Page 3 (first page)]

It has happened that an Englishman (forgetting all the names of places

in his own country ending in mouth) has regarded with a kind of

religious horror the number of parochial names in Ireland beginning with

the syllable Kill, as a sad, but apt indication, even in spirituals, of

the Hibernian proneness to truculence. The feeling would hardly be

diminished were it to be told, that a professed messenger of peace was

lecturing this evening on Swords, aye, and the same Swords in part

appropriated by ecclesiastical ordinance to the canonry of a church,

like St. Patrick's, where every stall exhibits the three great emblems

of war - the sword fixed, the helmet erected, and the banner waving in

defiant array.

Leaving such a display, were he to travel northwards, he would find a

townland in the county of Louth, bearing the kindred name of Glasspistol,

and draw very plausible conclusions as to the social condition of a

county where the voice of blood cried as it were from the very ground.

And yet he might be mistaken: the prefix "Kill" is nothing but an Irish

form of the Latin cella, a monastic term appropriated to the

idea, "Church;" and that, as originally employed by the most harmless of

mortals, the secluded hermit. The amusingly ominous name Glasspistyll is

a British compound, signifying "Green-stream," while the Swords

of this evening are as weak as water, though having the common attribute

of being drawn.

In fact, your name Swords, as borne by this parish of 9,674 acres, in

the barony of Nethercross, with 1,294 inhabitants in the town, and a

gross population of 2,962, signifies nothing more or less than "Pure,"

and belonged to the well, which being near the spot on which the

primitive church was founded, became in after times what is called "a

holy well," and gave its name to the church and parish at large.

The original word is properly written "Sord," or "Surd," which is

interpreted "clear," or "pure," although in modern Irish the word so

spelt bears the meaning of "order ... industry ... diligence." The w

came into it after the settlement of the English, who wrote the name

Swerds, though pronounced Swords, as the verb shew has the

sound of show. This interpretation which I give you is from an ancient

Life of St. Columbkille, preserved in a very venerable MS. of the Royal

Irish Academy, of the fourteenth century.

But, to afford you an instance of the danger and uncertainty of

conjectural derivation, I may mention, that I once met at a clerical

meeting a gentle man of sound scholarship, who gave me to understand

that Swords was a corruption of the Latin word Surdus, "deaf," it

being an appellation borrowed in the middle ages from a monastery or

hospital, which was founded here for the admission of superannuated

ecclesiastics who had lost their hearing. Upon which I could not resist

the temptation of creating a set off in the case of my own parish of

Lusk, which, on the spur of the moment, and with equal credibility,

I alleged was derived from the Latin Luscus, "blind of one eye,"

observing that as Swords was the asylum for the deaf, so Lusk was the

hospital for those of defective vision.

But in all seriousness, it was the practice of the early founders of

Christianity in these islands, when planting a church in any spot, to

have special reference to the proximity of a well. We could easily

understand how the existence

[Page 4]

of a well in an eastern clime would determine the choice of site for a

church; but in a cool and over-irrigated country like Ireland; it may be

somewhat more difficult to account for the great importance which was

attached to the well, and for the great number of holy wells, with their

stations, and patrons, and votive offerings, which came to be regarded

with religious veneration.

The famous Bishop Boniface writes to Pope Zachary in 745, complaining of

Adalbert, a Gaul, that he dissuaded men from visiting the Limina

Apostolorum, dedicating in his own honour oratories, and erecting

crosses and chapels in plains, and at wells, and ,wherever he

chose, and there persuaded them to celebrate public worship, till

multitudes of the people, setting other bishops at nought, and forsaking

the ancient churches, thronged to such places, saying, "The merits of

holy Adalbert shall aid us." I could tell you curious stories of the

supposed sanctity of wells, but they would divert me from the immediate

object of our lecture; suffice it to say, that well-worship existed in

the country before the introduction of Christianity, and that when the

people were converted, like the transfer of pagan temples, these wells,

with all their veneration, were made over to the aid of the new

religion.

Besides, the convenience of every-day life tells us how desirable it is

to have a good supply of pure water at hand, and we must bear in mind,

that ecclesiastics in old times were men of like passions as in the

present day, and required the same elements of sustenance for their life

and health.

Conspicious among the evangelical labourers in Ireland was St. Columba,

or Columbkille, whose genius and devotion have won for him a high place

in the annals of the Church of Christ. This man was born in Gartan, in

the county of Donegal, in 521. About the year 553 he founded the church

of Durrow, and previously to 563, when he departed from Ireland to Iona,

it is recorded that he founded your church of Swords.

The early Irish Life of him, to which I have already alluded, thus

relates the origin of your church and of its name "Columbkille founded a

church at Rechra (that is, the island of Lambay), in the cast of Bregia,

and left Colman, the Deacon, in it. Also he founded a church in the

place where Sord is at this day. He left a learned man of his people

there, namely, Finan Lobhar, and he left a gospel, which his own hand

wrote, there.

There also he dedicated a well named Sord, i.e., 'pure,' and he

consecrated a cross. One day that Columbkille and Cainnech were on the

brink of the tide, a great tempest raged over the sea, and Cainnech

asked, 'What saith the wave?' Columbkille answered, 'Thy people are in

danger yonder on the sea, and one of them has died, and the Lord will

bring him in unto us to-morrow to this bank on which we stand."

"As Bridget was one time walking through the Currach of Life (i.e., the

Curragh of Kildare), she viewed the beautiful shamrock-flowering plain

before her, whereupon she said in her mind, that if to her belonged the

power of the plain, she would offer it to the Lord of creation. This was

communicated to Columbkille in his monastery at Sord, whereupon he said

with a loud voice, 'Well has it happened to the holy virgin; for it is

the same to her in the sight of God as if the land she offered were in

her own right."' Hence St. Columba has always been regarded as the

founder and principal patron of the church of Swords. He died in 597, on

the 9th

[Page 5]

of June, and that day has been regarded as his festival in Scotland

as well as in Ireland. Accordingly, when, 600 years afterwards, the

privilege of holding a fair at Swords was conceded to the Archbishop of

Dublin by King John, the day chosen, or rather ratified, as previously

observed, was the feast of St. Columba, on the 9th of June.

And so intimately was the memory of the founder associated with the name

of the place, that almost the invariable designation of the church and

district was Sord-Columcille. But coupled with this

saint's name, there is another, which shares the ecclesiastical

patronage of the spot; and though but few particulars are recorded of

his history, there is sufficient evidence to prove that in his day he

was an ecclesiastic of considerable eminence.

This was St. Finan, surnamed Lobhar, or "the Leper." How strange

that such should be made a saint; but Christanity had long before

abolished the disabilities of the Leper, and with the fall of the Jewish

ordinal, arose the prospects of the bodily sufferer.

The Irish seem to have held such in veneration; and we can prove that

several of the most honoured names in our native calendar are men whose

skin was the scat of a loathsome disease, or whose features had been

levelled by the ravages of cancer.

St. Finan belonged to the former class, St. Mobhi (Movee), of Glasnevin,

styled the clarenach, or "flat- faced," is referable to the

latter; and in the great veneration which the ancient Irish always

entertained for extreme asceticism and self-denial, their respect for

those who suffered by the hand of God was not less when that compulsory

mortification was coupled with a holy life.

St. Finan the Leper was patron saint of three churches in Ireland,

namely: Swords; Ardfinnan, in the county of Tipperary; and Innisfallen,

in Loch Lene, or Killarney. The latter part of his life was spent at

Clonmore near Enniscorthy, in the county of Wexford, where he continued

for thirty years, all the while labouring under a sore disease, and

given up to pious contemplation, frequently enjoying rapturous visions.

He died here on the 16th of March, about 650, and was buried in this

monastery. Of him there is testimony in an exceedingly ancient Irish

poem, where it is said in reference to Clonmore:-

"There are two worthies whose bodies lie near the cross on the south,

St. Onchuo, who rose superior to the love of this fleeting world, and

St. Finan the Leper, the strenuous performer of good works."

His celebrity was early recognised in England; for in the Salisbury

Martyrology is the commemoration of "St. Finan the Bishop, a man of

singular sanctity, who, among other miracles, restored three dead men to

life." In Scotland, too, there is a memorial of his name. Sunart, which

lies near the south end of the Caledonian Canal, is known by the

ecclesiastical name of Ellen Finan, or "Finan's island," from the

parish church which is seated on an island in Loch Sheil. In this place

is preserved St. Finan's Bell, of iron, and of that square pattern, of

which so many examples are to be seen in our Museum of National

Antiquities.

It is well known that most of the west coast of Scotland was peopled

from Ireland in the early part of the sixth century. And the colonists

naturally took with them their native associations, and long maintained

a

[Page 6]

close relation with the mother country. One result was, that the

founders of Christianity in that territory were Irishmen, and their

names are borne by the churches which they founded. In 1857 I had a

letter from a Scotch Advocate, a zealous investigator of his national

antiquities, in which he says,

“Perhaps you will permit me to ask a question, which I have heard a good

deal agitated while on a visit in the Moidart part of Inverness- shire,

some weeks ago: Which of the St. Finans that appear among the Roman

Catholic saints, gives his name to Glenfinan in that part of the

country? There is a beautiful islet in Loch Sheil, running from

Glenfinan almost to the Western Ocean, called after the same saint,

Ellanfinan, on which are the ruins of an ancient church, and a

churchyard, where the inhabitants on both sides of the loch, and of both

faiths, still bury their dead. There is also a stone called St. Finan’s

Chair, on which tradition says the holy man sat down, and admired the

beautiful island on getting the first sight of it, as he came over the

Ardnamurchan hills from Iona. l have looked in vain into the books

here, &c.”

To this I replied, that as we had several Finans in the Irish Calendar,

he must endeavour to find out the day on which he was commemorated, and

then I might succeed in determining the saint in question.

After some months I received a second letter stating that, after the

most diligent local search, he had just succeeded in learning this much,

that a tradition existed in the place, that the saint’s festival was

either the day before, or the day after, St. Patrick’s Day. That is,

either the 16th or 18th of March.

Thus guided, I turned to our Calendar, and there, sure enough, I found

at March 16th, “S. Finan the Leper, of Sord and Clonmore.” Meanwhile I

had removed from Ballymena to Lusk, and having early made the

acquaintance of the neighbouring saints, I was able to inform my Scotch

correspondent, that I lived within four miles of the principal church of

this saint, whose memory reached to the confines of Argyle and

Inverness.

Further, Finan the Leper was of the race of Clan, son of Olill Olum, who

flourished in the year 234; and, as such, was a kinsman of St. Mac

Cullin, the founder and patron saint of Lusk, who died on the 6th of

September, 497; as also of St. Cianan, the founder and patron saint of

Duleek, who died November 24th, 488.

All these were the offspring of Fadhg, son of Cian, which Cian was the

progenitor of the race called the Cianachta, or “Descendants of Cian;”

one branch of whom settled in the east of Bregia, and occupied a

maritime tract, extending from Clogher Head southward to Clontarf, and

running inland about five or six miles. It is curious to find the family

location of saints, even at this early date, which foreshadowed the

system of lay presentation; both taking their rise from the principle,

that the original endower of a church was entitled to have the

nomination of the minister to serve therein.

Part of this territory of Cianachta was called Ard Cianachta by Adamnan,

in his Life of St. Columba, which he wrote about the year 690; and the

district described by him as extending from the Ailbene, or Delvin

River, to the River Liffey. In after-times, when the Danes settled in

Ireland, this district became occupied by them; and as they were styled

Sails, or “foreigners,” by the native Irish, their possessions acquired

the name of Fine Gall, that is, “the region of the strangers,” and the

name

[Page 7]

eventually became attached to it in the Ossianic form of Fingal, still

familiar to us; and giving the title of Earl in the Irish peerage to a

member of the Danish family of Plunket. The headquarters of the Danes in

Fingal were at Malahide, formerly called Inver Domnon; and the name of

this place is associated once in Irish record with the neighbourhood of

Swords.

In Moortown, which is about an English mile N.-W. of you, on the way to

Killossory, at the left-hand side of the road is a curious, sombre-looking

ruin, and in the adjacent meadow is a well, with an old tree

overhanging, and having all the appearance of a holy well.

This place is marked on the Ordnance Map as the site of the Abbey of

Glassmore, and the Well as St. Cronan’s, who founded a church here,

before the middle of the seventh century. St. Cronan was martyred on the

10th February, as appears from the old entry in the Calendar.

“Glassmore is a church near Swords, on the south; whither came the

Northmen of Inver Domnann, and slew both Cronan and his entire

fraternity in one night, so that they let no one escape; and there the

entire company was crowned with martyrdom.”

We have got so far now as the establishment of the following facts: the

Church of Swords was founded by St. Columba, about 550, in the region of

Keenaght, who placed there as its first minister St. Finan the Leper, a

member of the occupying tribe, and probably a native of the

neighbourhood.

After this, all records became silent, and we lose sight of the place

for some centuries. Meanwhile, however, we may be sure the seeds of

Christian religion once sown here were steadily bearing fruit- the

church becoming more deeply rooted, its influence spreading, its

endowments increasing, and its presence steadily operating against the

surrounding tendency to lawlessness and barbarity. It became at an early

date a little monastic establishment; not such as one would expect to

find, whose eye was accustomed to the stately fabrics of after-times,

when wealth and civilization lent their aid to the embellishments of

Christianity; but a little group of cold, comfortless cells, enclosed by

a circular entrenchment of earth and stone; having a plain oratory for

divine service, and a common apartment for their meals.

Wood formed, probably, a principal ingredient in the structure of these

primitive buildings, and everything was constructed on the simplest and

cheapest scale.

Swords does not appear in the Irish Annals until the year 965, when

their (sic) is recorded “the death of Ailill, son of Maenach, bishop

of Sord and Lusk.” At 1023 is recorded the “decease of Malmuire

0’Cainen, sage bishop of Sord Columcille.” At this period, and

previously, it was the custom of the Irish to have bishops resident in

their principal monasteries, who were often under the control of the

abbots, like the modern bishops in the Moravian Churches; and whose

functions were not so much the government of a diocese, as the

transmission of holy orders, and the performance of those rites peculiar

to the episcopal office.

Such we may believe to have been the case at Swords. There were no

territorial dioceses as yet established in Ireland; nor was it till near

the early part of the twelfth century that even an attempt was made to

partition Ireland into ecclesiastical districts, called dioceses.

Meanwhile Lusk and Swords were the two principal churches on this side

of Glendalough, and though Lusk had a much earlier and fuller succession

of bishops and abbots, still the

[Page 8]

sister church was one of considerable importance also. It rose, 1

believe, to this importance about the middle of the tenth century; and

it is to the beginning of that, or the preceding century, that 1 would

refer the erection of the round tower, which still remains the chief

curiosity, and indeed, only surviving relique of the ancient

ecclesiastical establishment of the place.

And it is remarkable to find these two churches of Lusk and Swords

vindicating their claim to antiquity, by the existence of these

memorials of a remote age; and, though but four miles asunder,

possessing the only structures of the kind, with the exception of

Clondalkin, in the county.

Another did indeed exist at St. Michael le Pole's Church, in Ship

Street, Dublin, near the back Castle gate; but has long since

disappeared. We may, therefore, regard Swords and Lusk as the

ecclesiastical capitals of the district, and the nucleus of the diocese

of Dublin. They are older than any church in the metropolis; and when

they were flourishing monastic establishments, the site of Dublin was a

muddy estuary, of neither note or importance.

Dublin was strictly a Danish city, and called into existence, as it was

afterwards maintained, by the invading Northmen. In such an institution

as the monastery of Swords we might expect an ample predial endowment,

in the way of lands. And so it was; and these lands were farmed by an

officer called a herenach, who was a kind of ecclesiastical

tenant, having high position in the monastery, and being generally in

holy orders.

At 1028, the Annals inform us, "died Gillapatrick O'Flaherty, herenach

of Sord." Again, in 1048, "Hugh, son of Maelan O'Nuadhat, was killed on

the Friday before Easter, in the middle of Sord."

In 1060, "Malkieran O'Robbacan, herenach of Sord Columkille, died;" and,

in 1136, "MacEravain, herenach of Sord, fell by the hands of the men of

Farney."

Now, these four are the only names of the herenachs of this church which

have come down to us; but they are sufficient to prove the existence in

this church of this ancient office, and, therefore, of all its monastic

accompaniments.

When the diocese in after-times became defined, the bishops got control

of all these herenach lands, the herenachs being put under rent to them;

and thus it happens as an almost general rule through Ireland, that

bishops' lands are to be found in the most ancient parishes, and

generally near old churches; for, in fact, the episcopal endowment

became a centralization, as it wore, of all the little monastic

settlements that were dotted over the country, which in their primitive

days, when wants were few, manners simple, and pretensions low,

afforded, each, abundant maintenance to its local superior.

But when bishops assumed a station of temporal importance, becoming

peers of Parliament, and the occupiers of stately palaces, then grew the

demand for increased revenues; and all the minor endowments were swept

into a common purse, which filled and swelled, till the monstrous

revenues of the episcopal body, in the last and early part of the

present century, threatened the existence, as they impaired the health,

of the Established Church.

The church lands of Swords and Lusk formed a large item in the rental of

the bishop, who at first had Glendalough as his episcopal seat; and

when, about the period of the English invasion, the Danish see of

Dublin, which extended no further than the city walls, became enlarged

with a suburban district, Swords and Lusk were transferred from the

see

[Page 9]

of Glendalough to that of Dublin. And in Pope Alexander Ill's bull to

St. Laurence O'Toole, in 1179, confirming his archiepiscopal see, the

churches of his diocese are enumerated, Lusca being the first,

and Sord the second. Swords then became the head of a rural

deanery; and thus preserved to some extent a shadow of its former

importance.

But the cultivation of literature was always an attribute of the Irish

monasteries, which were educational as well as devotional, and each had

its Ferleighin, or "man of lecturing," that is, a Lecturer or Professor.

The Annals notice two such at Swords. In 1042, "died Eochagan, herenach

of Slane, Lector of Sord, and a distinguished writer." His successor

came to a more violent end, for in 1056, "the fire of God (that is,

lightning) struck the Lector of Sord, and tore asunder the sacred tree."

After the battle of Clontarf, where Brian Boru fell in the arms of

victory, on Good Friday, 1014, his body was conveyed to Swords of

Columcille; whither, according to the Four Masters, came Malmurry, the

successor of Patrick, that is, Bishop of Armagh, with his clergy; and

they carried from thence the body of Brian, King of Ireland, and that of

Murragh his son, and the heads of Conary and Mothia.

Another collection (the Annals of Innisfallen) varies in the details,

and states that the monks of Sord Columcille, hearing that Brian had

fallen in the battle, came on the following day, and carried his body to

Sord, and thence to Duleck of St. Kienan; the clergy of which conveyed

it to Louth, where they were met by Malmurry and his clergy, who carried

the sovereign's body to Armagh, and buried it there.

In the interval between 993 and 1166, Swords was burned and wasted by

various hands.

993, "Sord of Columcille was burned by Maolsechlain."

1016, "Sord of Columcille was burned by Sitric, son of Aniat, and the

Danes of Dublin."

1020, "Sord of Columcille was plundered by Connor O Maclachlann, who

burned it, and carried away many captives, and vast herds of cows."

1031, "Sord of Columcille was burned and plundered by Connor

O'Maclachlann, in revenge for the death of Raghnall, son of Ivar, Lord

of Waterford, by the hand of Sitric, son of Anlaf."

1045, "An army was led by M'Eochaidh and Maolsechlann, with the

foreigners who burned Sord, and wasted Fingall."

1069, "Lusc and Sord of Columcille were burned."

1102, "Sord of Columcille was burned."

1130, "Sord of Columcille, with its churches and relics, was burned."

1138, "Sord burned."

1150, "Sord burned."

1166, "Sord of Columcille was burned."

This is the last mention of the name in our Irish Annals. Six years

afterwards, the English subjugated Ireland; and Fingall presently

yielded to their sway, so that the native annalists lost sight of it;

and henceforth we consult another class of records for the continuation

of its history.

But before we pass from the Irish to the English occupation, let us

observe that, in 1130, Swords was possessed of several churches. Now it

contains but one, at least on an old site. Those churches seem to have

been but a short way asunder, and within the limits of the present town.

[Page 10]

The Documents of a later date give us the names of two chapels, which

probably represented these earlier structures. One of these was a

chapel, dedicated to St. Finian, which, with its adjoining cemetery, was

situated on the south side, near the Vicar's manse, on the road to

Furrows, or Forest, as it is now called, lying to the south-west.

The other was St. Bridget's Chapel, on the north side of the town,

adjoining the Prebendary's glebe, and not far from the gates of the old

palace; near to which was an ancient cross, called "Pardon Crosse."

The former of these was standing in 1532; but the latter was in ruins at

that date; and Archbishop Alan observes that beside it were two burgages,

which were let to the Monastery of Holmpatrick at Skerries. The ground

occupied by the latter of these chapels now belongs to the economy lands

of the parish; the site of the former is the space occupied by the modem

glebe house.

But we must return to the transition period of the Irish Church, namely,

the English invasion in 1172, when ecclesiastical matters, especially in

the diocese of Dublin, underwent an important change. St Lawrence

O'Toole, the last native Irish Bishop for a long period, died in 1180,

at Eux, in Normandy, whither he went to deliver the son of Roderick

O'Connor, king of Connaught, as a hostage for the tribute his father

agreed to pay the king.

An Englishman called John Comyn was appointed to succeed him in 1181,

being a favourite with the king of England, and an assiduous promoter of

the English interest, he was handsomely rewarded, and obtained several

grants and immunities for his see.

At this time, Swords was one of the principal churches in the diocese,

and contributed largely to the Archbishop's income. As a benefice, it

was of great value; and being what was styled a plebania, or

"mother church," it possessed a great number of dependent chapelries,

some of which still continue in union with it, though others have been

detached.

This Archbishop on one occasion presented his kinsman, Walter Comyn, to

the parsonages of the churches of St. Columcille and St. Finan, of

Swords; with the appendant chapels of Cloghran, Killechni (Killeek),

Killastra (Killossory), Donaghbata (Donabate), Malahida, Kinsale,

Ballygriffin, and Coloke.

Of these, Cloghran, Donabate, Balgriffin, and Culock, were separated

from it at an early date, but Malahide continued in union much later;

and Killossory, Killeck, and Kinsaley, still form part of the union; the

Incumbent being Vicar of Swords and Kinsaley, but Curate of Killossory

and Killeck.

Rich and fat as this great benefice thus became, it was natural that,

like the fine parishes of Winwick and Stanhope in England, it should be

eagerly sought by these of high and influential connections. In 1302,

William de Hothum, a nephew of the Archbishop, enjoyed it.

In 1366, the famous William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester, and

Chancellor, held it together with eleven benefices in England. And in

1423 it was even a fit object for transmontane endowment; for Brande,

Cardinal of Placentia, was nominated to it by Henry IV; and the writ,

directed to the Archbishop, commanded his to assign to the Cardinal a

stall in the choir, and voice in the chapter.

In like manner, Lusk was once a great and lucrative benefice, so much

so, that King Edward I thought it worth conferring, in 1294, upon James

of Spain, nephew of his Queen Eleanor. Lusk was

[Page 11]

another plebania, and embraced, besides the present parish, all

Balrothery and Balduncan. How the times are altered, when my friend, Mr

Twigg, and myself, are all that are to be shown for a Cardinal and a

Queen's nephew!

But I forgot to mention, that in 1190, when the collegiate church of St.

Patrick's was founded, Swords was named as its first canonry; and among

its endowments, were the tithes of all the Archbishop's mills, except

that of Swords, which had previously been granted to the Nunnery of

Grace Dieu (de Gratia Dei), in Lusk parish, on the borders of Swords; it

being the Archbishop's first foundation, and indicative of religious

gallantry in giving precedence to the gentler sex. In 1219 it became a

pre- bend, in the remodelled foundation.

But, as I have observed, it grew to be very rich; its large income,

arising out of its considerable demesne, and the tithes issuing from a

wide and fertile district. It was, therefore, called (after the style of

Sarum and Durham) the golden prebend; being, as Archbishop Alan

observes, as it were, a sack virtually full of gold. Therefore it was,

that in 1431, Arch- bishop Richard Talbot formally divided it; his

motive being, as it is said, "that it was sought too zealously by

cardinals, and other minions of the Papal See."

It was parted into three unequal portions-namely, one part to the

Prebendary, the second to the Vicar, and the third to the Economy of St.

Patrick's. Out of the last portion were to be maintained six vicars, and

six choristers, and the residue to be expended in furnishing lights,

repairs, and the defraying of necessary expenses.

The charters which the Archbishops of Dublin obtained from the new Lords

of Ireland, not only confirmed them in the possession of the lands

hitherto belonging to the See, but also conferred upon them feudal

dignities and increased powers. Thus, in 1192, the Archbishop obtained a

patent, authorizing him to hold in his manor of Swords an annual fair,

commencing on St. Columba's Day (June 9), and lasting a week. The tolls

arising from this proved a source of considerable emolument.

About this time - namely, 1200 - the castle was built. An Inquisition of

1265 finds that a constable was there in John Comyn's time.

In 1216 the manor of Swords, with fresh privileges and enlarged

possessions, was granted by King Henry 111 to Henry de Loundres, the

second English archbishop, on condition that he should build and

maintain a castle on his manor of Castlekevin, with a view to defend the

pale in that quarter from the invasions of the great Wicklow

families-the O'Byrnes and O'Tooles.

Coming into this country as a conquering race, and introducing new laws

and customs, the English settlers required places of refuge, and depots

for property, in the midst of an oppressed and exasperated people.

Hence, the lord of the manor not only needed security for himself and

his immediate retainers within his crenelated walls, but felt it his

interest, by the military influence of his fortress, to crush the

refractory, and overawe the surrounding country; while, in cases of

emergency, it afforded shelter to those in danger.

John Comyn, the first English Archbishop, was a strenuous instrument in

the extension of English rule. For which reason the see became possessed

of unusual privileges, and the Archbishop grew to be one of the most

powerful barons in the kingdom.

[Page 12]

Seized of considerable estates in Swords, Lusk, and several adjacent

parishes, he and his successor, Henry, felt the importance of their

position in Fingall; so that this mansion of Swords served not only as a

tower of strength, but a store-house of English civility and law for the

territory, and withal a wholesome check upon the excesses of the

neighbouring temporal barons.

On this manor the Archbishop had his own seneschal, who was exempt from

all interference of the sherifi of the county, and the courts of law. He

had the right to try every plea, except the four pleas of the crown. He

had his gallows on an eminence near the town, afterwards known as the

Gallows’ Hill, where many a male-factor paid the penalty of his life for

his misdeeds; and every writ which issued from the civil courts was

transferred from the sheriff to his seneschal, ere it could be served.

In fact, he was a little king in his principality.

But being an ecclesiastic, and, as such a man of letters, and a father

of his clergy, the military development was rather an accident of office

than an essential attribute; consequently, the archiepiscopal abode

required to be such as would afford scope for the accommodation of a

brotherhood, and the exercise of religion-frowning battlements without,

but smiling peace within. Thus the palace of Swords demanded space, that

it might embrace within it the appliances of religion and peace.

At the present day we are able to form a tolerable estimate of the

original strength and internal proportions of the premises, for the

outline externally is perfect, and a considerable share of the old pile

remains within- more, indeed, than might have been expected in a country

where the demolition of ecclesiastical remains, and wanton contempt for

things venerable, have seldom been attended by censure or

discouragement. What the original character and contents of Swords’

castellated palace were, we learn from an interesting Extent of the

archiepiscopal manors, preserved in Archbishop Alan’s Register, called

the Liber Niger.

In 1326, Alexander de Bicknor, the Archbishop, having displeased the

king, and further, being greatly in arrear in his accounts as Lord

Treasurer, the king seized into his hands the profits of the see, in

satisfaction for the deficiency; and, in order to ascertain the

available amount, Inquisitions by jurors were held before the Sheriff in

the various manors.

That on Swords was sped at Dublin, on the 14th March, 1326, and twenty

jurors were empanelled. The result of their finding, as regards the

palace of Swords, was as follows:-

“Who being sworn, say on their oath, that there is in this place a hall,

and the chamber adjoining said hall, the walls of which are of stone,

crenelated after the manner of a castle, and covered with shingles.

“Further, there is a kitchen, together with a larder, the walls of which

are of stone, roofted with shingles. And there is in the same place a

chapel, the walls of which are of stone, roofed with shingles. Also

there was in the same place a chamber for friars, with a cloister, which

are now prostrate. Also, there are in the same place a chamber, or

apartment, for the constables by the gate, and four chambers for

soldiers and wardens, roofed with shingles, under which are a stable and

bake-house.

“Also, there was here a house for a dairy, and a workshop, which

[Page 13]

are now prostrate. Also, there is on the premises in the haggard a shed

made of planks, and thatched with straw. Also, a granary, built with

timber, and roofed with boards. Also, a byre, for the housing of farm

horses and bullocks.

"The profits of all the above-recited premises, they return as of no

value, because nothing is to be derived from them, either in the letting

of the houses, or in any other way. And they need thorough repair,

inasmuch as they are badly roofed."

Thus we perceive that so early as 1326, these buildings were beginning

to suffer from the effects of time.

In 1380, the manor of Swords was seized again into the king's hands by

Sir Nicholas Daggerworth, a Commissioner of Forfeitures, on the plea

that the conditions of 1216 had not been fulfilled. In the return,

however, of said Sir Nicholas to a writ de certiorari, he

confessed that cause had not been shown why the said manor should be so

seized.

Accordingly, a writ of restitution to Robert de Wykeford, the

Archbishop, was issued by the Treasurers and Barons of the Exchequer.

There is no evidence that this place was repaired so as again to become

a residence of the Archbishop. Probably it was not, for in 1324 was

erected by Alexander de Bicknor the archiepiscopal palace of Tallaght,

in the south part of the county, which for centuries continued to be

employed as the country scat of the Archbishop.

And it was not till 1821that it formally ceased to be regarded as a

palace, and its adjuncts as manorial land, when an Act was passed,

divesting the Archbishop of it, and placing the premises in the same

condition as ordinary church property. It is to be observed that the

site of the palace of Tallaght is now occupied by a nunnery.

Swords Castle had ceased to be regarded as a palace ages before this.

Connected with this stronghold was the office of Chief Constable, which

was considered as one of importance, and long survived the occupation of

the castle. In 1220, William Galrote filled the situation.

In 1240, Sampson de Crumba. Thomas Fitzsimons, of Swords, was constable

in 1547. In this year the reversion of the constableship was conveyed to

trustees in the minority of Patrick Barnewall, of Grace Dieu; and

afterwards, the office and endowments descended to his son, Sir

Christopher Barnewall, who, in 1563, conjointly with the Archbishop, by

consent of the two cathedral Deans and Chapters, granted, in trust, to

Richard Fagan, of Dublin, the office of constable of the castle or manor

of Swords, with all appurtenances, lands, and endowments, to hold for

ever, with power to appoint deputies; and in lieu of the salary of £5,

Irish, to have two acres of meadow in the Broad mead, to the said office

appertaining, and all messuages, lands, and fishings whatever, in New

Hagard in the parish of Lusk, and Rogerstown in the parish of Swords.

In 1624, Patrick Barnewall, of Grace Dieu, obtained pardon for

alienation of certain interests, and, among them, this of the

Constableship of Swords, with ten acres in the Broad meadow, to the said

office belonging. With this constableship, it is likely that the tenancy

of the premises also was vested in the Barnewalls, whose interest

therein seems to have given rise to the tradition, that Lord Kingsland,

in consideration of his

[Page 14]

holdings under the See of Dublin, was bound to wait on the Archbishop

whenever he visited Swords, and to hold the stirrup, as His Grace

mounted or dismounted. The old palace is still hold under the See of

Dublin.

In later years, the only officers who have exercised jurisdiction within

the Corporation were a portreeve, and the seneschal of the manor of St.

Sepulchre's. The portreeve was appointed by the Archbishop, and annually

sworn in at the Michealmas courtleet in Dublin, before the Seneschal of

St. Sepulchre's. He has no salary nor emolument except the annual profit

of three acres of land, near the town, for which he receives about £8 a

year. The portreeve formerly held a court here once in the week,

entertaining all claims within the manor, but otherwise without limit.

His authority, however, having been questioned, he has wholly

discontinued to act, and the ordinary Petty Sessions Court is now the

only town jurisdiction. The manor of Swords embraced, not only the

Archbishop's properly here, but his lands in Lusk, Clonmethan, and the

neighbouring parishes; and lately, when the south commons of Lusk were

enclosed by Act of Parliament, the sum of £2,000, awarded as

compensation, was claimed by the Archbishop, as lord of the manor, and

at first allowed, but afterwards disallowed, and adjudicated to the

parishioners by the Court of Chancery; and thus we see the gradual

declension of church secularities, until, in the present day, almost all

the feudal privileges of the church have been abolished.

Proportionate with the decline of the Archbishop's influence in Swords,

seems to have been the rise of the popular element. In 1578, Queen

Elizabeth incorporated the borough and invested it with municipal

rights. Among these was the privilege of returning two members to

Parliament, the franchise being enjoyed by burgesses, who for their

burgages paid an annual rent of twelve pence.

The first members who represented Swords were Walter Fitzsymonds, of

Ballymadroght, and Thomas Taylor of Swords, Esqrs. They were returned in

April, 1585. From that time, we find the names of Blakeny, Taylor,

Tichbourne, Reading, Molesworth, Plunket, Bolton, Cobbe, Hatch,

Beresford, Massey, and Synge, representing the potwallopers, or

occupants of houses resident in the borough, being Protestants, who were

of the meanest class of citizens, and whose venality was as black as the

pots that qualified them.

A writer in 1798 thus humorously describes the experiments resorted to

by candidates, on the eve of an election:-

"General Eyre Massey, some time since, cast a longing eye on this

borough, which he considered as a common open to any one occupant, and

to secure the command of it to himself, he began to take and build

tenements within its precincts, in which he placed many veteran

soldiers, who having served under him in war, were firmly attached to

their ancient leader. Mr. Beresford, the first Commissioner of the

Revenue, who has a sharp look out for open places, had formed the same

scheme with the General, of securing this borough to himself; and a

deluge of revenue officers was poured forth from the custom-house to

overflow the place, as all the artificers of the new custom-house had

been exported in the potato-boats of Duncannon, to storm that borough.

The wary General took the alarm, and threatened his competitor, that for

every revenue officer appearing there he would introduce two old

soldiers, which somewhat

[Page 15]

cooled the first commissioner's usual ardour; thus the matter rests at

present; but whether the legions of the army, or the locusts of the

revenue, will finally remain masters of the field, or whether the rival

chiefs, from an impossibility of effecting all they wish, will be

content to go off like the two kings of Brentford, smelling at one rose;

or whether Mr. Hatch's interest will preponderate in the scale, time

alone can clearly ascertain."

In 1783, Charles Cobbe and John Hatch had been returned, but the upshot

of the election in 1790 was that Hatch was beaten, and the two rivals

both admitted to the enjoyment of parliamentary honours.

Out of the £15,000 which was awarded as compensation for the borough

disfranchisement at the Union, have grown this school and its

endowments. Would that the Union had in every instance brought forth

such wholesome fruits. Fortunately, there were no wealthy masters here

to claim this sum; so a public institution was founded, and the poor,

for once, got the benefit of a wise and liberal disposition of public

money.